I just finished the project (thanks Kolourpaint and Gifski). I started it last Sunday. I am therefore only addressing early adopters for the moment. I think there are a lot of people who would like to add a GUI to their existing projects. But they don't want or don't have the time to or are afraid to learn how to use a GUI toolkit. List of Rust libraries and applications. An unofficial experimental opinionated alternative to crates.io.

Hi HN !I created the Pyrustic framework [1][2] and built a few applications with it, including Hubstore [3] to connect users to applications.

I wondered if it was possible to make GUI dev even easier. I thought of a GUI builder, with drag and drop and everything that surrounds it. My current idea is complex to build, I hate using GUI builder, so the one I am going to create should be the one I will love to use. So I tried to create an intermediate product... Something between a GUI builder and a raw framework beast: Dresscode !

I just finished the project (thanks Kolourpaint and Gifski). I started it last Sunday. I am therefore only addressing early adopters for the moment.

I think there are a lot of people who would like to add a GUI to their existing projects. But they don't want or don't have the time to or are afraid to learn how to use a GUI toolkit. By the way, I'm writing a tutorial [4] to help them get interested in GUI dev. In the meantime, there is Dresscode !

Dresscode allows you to easily add a GUI to your project (next one or existing one) without altering the existing code base. And no need to learn how to use a GUI toolkit !

I hope this project will be useful to a lot of people and that it will make some of them want to use the Pyrustic framework to have full control over the GUI. Pyrustic could be like C, and Dresscode could be like Python :)

Your feedback is highly appreciated! [5]

[1] https://github.com/pyrustic/pyrustic/#readme

[2] https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=23930255

[3] https://github.com/pyrustic/hubstore

[4] https://github.com/pyrustic/pyrustic/#tutorial

[5] http://sl4.org/crocker.html

vignettes/gganimate.Rmd

gganimate is an extension of the grammar of graphics, as implemented by the ggplot2 package, that adds support for declaring animations using an API familiar to users of ggplot2.

Gif Skip

The following introduction assumes familiarity with ggplot2 to the extent that constructing static plots and reading standard ggplot2 code feels natural. If you are new to both ggplot2 and gganimate you’ll benefit from exploring the trove of ggplot2 documentation, tutorials, and courses available online first (see the ggplot2 webpage for some pointers).

Your First Animation

Gifski Debian

We’ll jump right into our first animation. Don’t worry too much about understanding the code, as we’ll dissect it later.

You go from a static plot made with ggplot2 to an animated one, simply by adding on functions from gganimate.

❗ transition_states() splits up plot data by a discrete variable and animates between the different states.

As can be seen, very few additions to the plot results in a quite complex animation. So what did we do to get this animation? We added a type of transition. Transitions are functions that interpret the plot data in order to somehow distribute it over a number of frames. transition_states() specifically splits the data into subsets based on a variable in the data (here Species), and calculates intermediary data states that ensures a smooth transition between the states (something referred to as tweening). gganimate provides a range of different transitions, but for the rest of the examples we’ll be sticking to transition_states() and see how we can modify the output.

Easing

When transition_states() calculates intermediary data for the tweening, it needs to decide how the change from one value to another should progress. This is a concept called easing. The default easing is linear, but others can be used, potentially only targeting specific aesthetics. Setting easing is done with the ease_aes() function. The first argument sets the default easing and subsequent named arguments sets it for specific aesthetics.

❗ ease_aes() defines the velocity with which aesthetics change during an animation.

Labeling

It can be quite hard to understand an animation without any indication as to what each time point relates to. gganimate solves this by providing a set of variables for each frame, which can be inserted into plot labels using glue syntax.

❗ Use glue syntax to insert frame variables in plot labels and titles.

Different transitions provide different frame variables. closest_state only makes sense for transition_states() and is thus only available when that transition is used.

Object Permanence

In the animation above, it appears as if data in a single measurement changes gradually as the flower being measured on somehow morphs between three different iris species. This is probably not how Fisher conducted the experiment and got those numbers. In general, when you make an animation, graphic elements should only transition between instances of the same underlying phenomenon. This sounds complicated but it is more or less the same principle that governs makes sense to draw a line between two observations. You wouldn’t connect observations from different iris species, but repeated observations on the same plant would be fine to connect. Same thing with animations.

Just to make this very clear (it is an important concept). The line plot equivalent of our animation above is:

Ugh…

So, how do we fix this and tell gganimate to not morph observations from different species into each others? The key is the group aesthetic. You may be familiar with this aesthetic from plotting lines and polygons, but in gganimate it takes a more central place. Data that have the same group aesthetic are interpreted as being linked across states. The semantics of the group aesthetic in ggplot2 is such that if it is undefined it will get calculated based on the interaction of all discrete aesthetics (sans label). If none exists, such as in our iris animation, all data will get the same group, and will thus be matched by gganimate. So, there are two ways to fix our plot:

- Add some aesthetics that distinguish the different species

- Set the group directly

❗ The group aesthetic defines how the data in a layer is matched across the animation.

In general 2) is preferred as it makes the intent explicit. It also makes it possible to match data with different discrete aesthetics such as keeping our (now obviously faulty) transition while having different colour for the different species)

Enter and Exit

While we may have made our animation more correct by separating the data from the different species, we have also made it quite a bit more boring. Now it simply appears as three static plots shown one at a time, which is hardly an attention grabber. If only there were a way to animate the appearance and disappearance of data…

Enter the enter and exit functions. These functions are responsible for modifying the state of appearing (entering) and disappearing (exiting) data, so that the animation can tween from and to the new state. Let’s spice up our animation a bit:

❗ enter and exit functions are used to modify the aesthetics of appearing and disappearing data so that their entrance or exit may be animated.

gganimate comes with a range of different functions, and using the enter_manual() and exit_manual() functions you can create your own. Enter and exit functions are composable though, so you can often come pretty far by combining preexisting ones

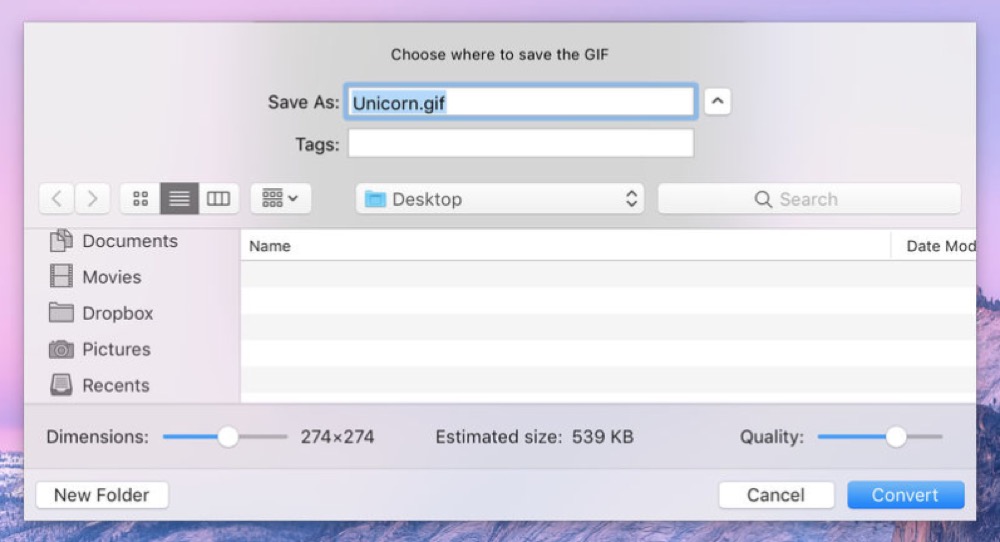

Rendering

In the examples above the animations has simply appeared when we printed the animation object, just like we would expect from ggplot2. As a lot of things are happening automatically, and you might want to take control, this section will give a brief overview of the rendering.

gganimate’s model for an animation is dimensionless in the same way as ggplot2 describe plots independent of the final width and height of the plot. This means that the final number of frames and its frame-rate are only ever given when you ask gganimate to render the animation. When you print an animation object the animate() function is called on the animation with default arguments, some of which are:

Gifski_renderer

- nframes sets the number of frames (defaults to

100) - fps sets the number of frames (defaults to

10) - dev sets the device used to render each frame (defaults to

'png') - renderer sets the function used to combine each frame into an animate (defaults to

gifski_renderer())

There are other arguments as well (e.g. ... will be passed on to the device so you can set width, height, dpi, etc), but these are the most important. If you don’t like the defaults you can either call animate() directly with values of your choosing, or modify the defaults by setting new with options(gganimate.<argument> = <value>).

A topic that requires some additional words are the renderers. The default will use gifski to combine the frames into a gif. gifs are great because they are virtually supported everywhere, and gifski is both a very fast, and very high quality converter. Still, you may have reasons to want a different output. gganimate is quite agnostic to how you want to combine the frames and, while it comes with a set of predefined renderers, any function that takes a vector of paths to image files along with a frame-rate, will do. The return value of your renderer is what is ultimately returned by the animate() function.

Below are a couple of examples of different animate() calls:

If you need to save the animation for later use you can use the anim_save() function. It works much like ggsave() from ggplot2 and automatically grabs the last rendered animation if you do not specify one directly.

Gifski C#

Want more?

This guide is far from exhaustive, but have hopefully given you a broad understanding of how gganimate works. There are still more to explore as we have only scratched the surface of transitions, let alone mentioned views and shadows. But for now this is left to you. There is a fantastic joy in discovery and with the things you have now learned you are ready to go digging on your own.