© TheStreet What is Coinsurance and How Is it Different From Copay?

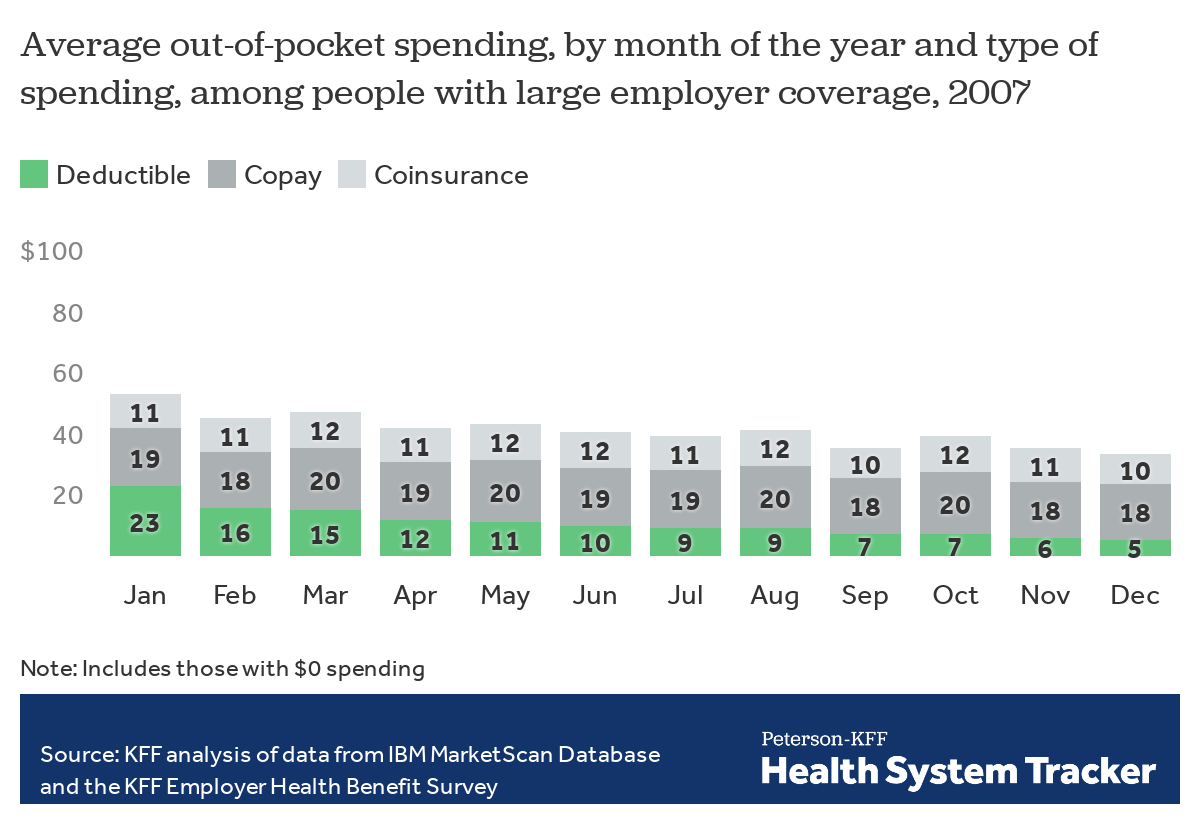

Those employed at small firms pay 39% of the premium for family coverage compared to 28% for workers at large companies. In 2017, the average family premium for Employer Sponsored Insurance (ESI) coverage was $17,581. Employers cover most of the cost, with workers covering 31% of the cost. Copay in Health Insurance refers to the percentage of the claim amount that has to be borne by the policyholder under a health insurance policy. Few insurance policies come with a mandatory clause for copayment, while others offer policyholders the option for voluntary copayment, which allows them to reduce their premium payment.

For such an important part of the average American's life, health insurance can get incredibly, frustratingly complicated. Rather than simply having the comfort of knowing you are covered for your medical needs, you're expected to understand a variety of terms in order to know what's covered, how much you're covered for and what you'll have to pay for.

One such term is coinsurance, a vague term without any added context. But coinsurance involves both you and your insurance provider, and so it's important to understand what it is and how it functions in the insurance process. Should you require a medical procedure, knowing your coinsurance can help you get a better approximation of how much you'll have to pay, and where to go from there.

So what is coinsurance, and what separates it from other figures in your health insurance?

What Is Coinsurance?

Among private sector employees enrolled in employer-sponsored health insurance, 68.2 percent had a co-pay for each doctor visit with an average co-pay of $23. In addition, 26.1 percent had a coinsurance percentage that averaged 18.9 percent. Here are the statistics for average individual monthly health insurance premiums based on tiered-plan choice: Catastrophic: $195. Catastrophic insurance covers essential health care benefits only. A bronze plan has low monthly payments for basic health care benefits and a. Home health care. $0 for home health care services. 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for Durable Medical Equipment (DME) Glossary. $0 for Hospice care. You may need to pay a Copayment of no more than $5 for each prescription drug and other similar products for pain relief and symptom control while you're at home.

Coinsurance is the amount you will pay for a medical cost your health insurance covers after your deductible has been met.

Your deductible, if you weren't aware, is the amount you have to pay before insurance kicks in to help pay. In health insurance, your deductible can get spread to multiple costs or one single cost until it runs out. Once you've reached your deductible, that's when insurance comes in. But in healthcare, you also have the coinsurance to deal with.

Coinsurance is measured as a percentage of what you will pay of the remaining costs compared to what insurance will. Perhaps the most common percentages here are 80/20 - that is to say, your provider will pay 80% of it, and you will pay 20%. Another common set up is 70/30 (you pay 30%).

Coinsurance comes into play when your deductible runs out, and depending on your deductible and your medical history, that amount of time could fluctuate wildly. Someone with a history of medical issues may choose a lower deductible plan (though these tend to have higher premiums) because they anticipate future costs, while someone without a troubling history may be more willing to enroll in a high deductible health plan to avoid high premiums, under the assumption that it is unlikely something major will come up.

Does Your Coinsurance Affect Out-of-Pocket Maximums?

Knowing your deductible is crucial for your health insurance, but once you've reached the end of your deductible you should know your out-of-pocket maximum. That is the maximum amount of overall money you have to pay before your insurance company covers all of the costs.

The money you are personally paying when coinsurance gets factored in does, in fact, go toward your out-of-pocket maximum. So let's say you have a deductible of $1,500 and an out-of-pocket maximum of $5,000. You reach that deductible, and the remaining medical costs you owe lead to $300 out of your own pocket due to coinsurance. Combined, this would mean you've paid $1,800 of your $5,000 out-of-pocket maximum.

So while coinsurance can be a bit of a nuisance, more money you have to take from your own pocket put toward medical costs, it is supposed to have a beneficial purpose of bringing you closer to your maximum. How much your out-of-pocket maximum will be will depend on the sort of insurance plan you end up enrolling in.

Example of Coinsurance

Video: How banks actually make money (CNBC)

Let's bring a few figures in to provide a real-life example. Let's say that your healthcare plan has a deductible of $1,000, and you have an 80/20 coinsurance clause.

With this information, say you incur $2,500 in medical costs. You haven't had to use your deductible prior to this, so all $1,000 of it goes toward this cost. From there, we're left with $1,500. How much of this will you be paying via the coinsurance clause?

$1,500 x 20% = 1,500 x 0.2 = $300

Your coinsurance payment here would be $300. Combined with your deductible, that means you would be paying $1,300 to the insurance company's $1,200.

This is why understanding your coinsurance clause is crucial. You're paying much less than you would without insurance, but in this example you still had to pay for more than half of the costs.

If you end up with other medical costs that your insurance covers, though, your deductible is no longer a factor and you would just have to pay the 20% via your coinsurance clause. So if your next medical costs that year are $1,200, you'd only pay $240 of it.

These, however, may be minor examples compared to what medical expenses you may have to deal with. You still have to reach your out-of-pocket maximum before your insurance company starts to cover 100% of the costs. Generally, your out-of-pocket maximum correlates inversely with your premiums. Much like with deductibles, those with higher premiums have lower maximums and those with lower premiums will likely have higher ones.

Coinsurance vs. Copay

Coinsurance and copay, as similar-sounding terms for your healthcare, may be a little confusing. Though they share similarities, they're ultimately different plans for your insurance.

Whereas coinsurance is the percentage you pay for medical costs after your deductible, your copay is a set amount you have to pay for other covered expenses. For example, a prescription medicine can have a copay, as can a physical or other visit to your primary care physician (PCP). Where a coinsurance plan might have you pay 20% for this doctor's visit, a plan with a copay may instead require you to pay a flat fee of $20 while they pay for the rest of it. Depending on the specific figures involved in your specific plan, a copay could be more or less than what the coinsurance is for any given medical cost.

That said, in other ways coinsurance and copay plans are quite similar. Generally copayments, like coinsurance, do not go toward your deductible but do go toward your out-of-pocket maximum.

Coinsurance in Other Insurance Industries

Coinsurance is most prevalent in the health insurance industry. But coinsurance is a way for insurance companies to try and mitigate risk in the event that expenses add up more than they anticipated, so it's not uncommon for you to find coinsurance in other insurance industries as well.

For example, you may find a coinsurance clause when dealing with property insurance. In this industry, the coinsurance dictates that the property must be insured for a percentage of its value. This is particularly common in commercial property.

Much like in health insurance, 80% coinsurance is the most common percentage. That meant if you had a $500,000 property, you would need to insure it for, at the very least, $400,000.

Let's say, though, that you didn't do that. You decided to only insure it for $300,000 in an attempt to save money on the deal. This could lead to a costly coinsurance penalty if something goes wrong.

You should have insured it for $400,000 but only went as far as $300,000 to insure your property (and you have a deductible of $2,000). Now let's say a pipe bursts in the building, causing excessive damage that totals up to $200,000. Your insurance will, when reviewing the case, notice you did not get the amount of insurance the coinsurance clause required and will impose a penalty.

To figure out the penalty, your insurance will divide the amount of insurance you got by how much you were supposed to (in this case, 300,000/400,000 or 0.75) and multiply that by your damage. 200,000 x .75 = $150,000, which is how much your insurance will pay. Thus, here your coinsurance penalty is a whopping $50,000.

This article was originally published by TheStreet. Cite this

Cite thisWhat you need to know about mental health coverage

When it comes to our well-being, mental health is just as important as physical health. Unfortunately, insurers haven’t always seen it that way. In the past, many health insurance companies provided better coverage for physical illness than they did for mental health disorders.

A law passed in 2008, the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (also known as the mental health parity law or federal parity law) requires coverage of services for mental health, behavioral health and substance-use disorders to be comparable to physical health coverage. Yet many people still aren’t aware that the law exists or how it affects them. In fact, a 2014 APA survey found that more than 90 percent of Americans were unfamiliar with the mental health parity law.

This guide helps you learn what you need to know about mental health coverage under the mental health parity law.

What does the law do?

The federal parity law requires insurance companies to treat mental and behavioral health and substance use disorder coverage equal to (or better than) medical/surgical coverage. That means that insurers must treat financial requirements equally. For example, an insurance company can’t charge a $40 copay for office visits to a mental health professional such as a psychologist if it only charges a $20 copay for most medical/surgical office visits.

The parity law also covers non-financial treatment limits. For instance, limits on the number of mental health visits allowed in a year were once common. The law has essentially eliminated such annual limits. However, it does not prohibit the insurance company from implementing limits related to “medical necessity.”

What health plans does the law affect?

The federal parity law generally applies to the following types of health insurance:

- Employer-sponsored health coverage, for companies with 50 or more employees

- Coverage purchased through health insurance exchanges that were created under the health care reform law also known as the Affordable Care Act or “Obamacare”

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Most Medicaid programs. (Requirements may vary from program to program. Contact your state Medicaid director if you are not sure whether the federal parity law applies to your Medicaid program.)

Some other government plans and programs remain exempt from the parity law. Medicare, unlike Medicaid, for instance, is not subject to the federal parity law. And some state government employee plans (including ones that cover teachers and employees of state universities, for instance) may opt out of the parity requirements.

How do I know if my health insurance plan provides mental health coverage?

Check your description of plan benefits—it should include information on behavioral health services or coverage for mental health and substance-use disorders. If you still aren’t sure, ask your human resources representative or contact your insurance company directly.

My insurance plan doesn’t have mental health benefits. Is that a violation of the parity law?

The parity law does not require insurers to provide mental health benefits—rather, the law states that if mental health benefits are offered, they can’t have more restrictive requirements than those that apply to physical health benefits. Fortunately, the vast majority of large group plans already provided mental health benefits before the parity law took effect. In addition, the Affordable Care Act requires that plans offered through the health insurance exchanges cover services for mental health and substance-use disorders.

Are all mental health diagnoses covered by the parity law?

Unlike some state parity laws, the federal parity law applies to all mental health and substance-use disorder diagnoses covered by a health plan. However, a health plan is allowed to specifically exclude certain diagnoses—whether those diagnoses are considered to be in the physical/medical realm or behavioral/mental health. Any exclusions should be made clear to you in your plan’s description of mental health benefits. If you are uncertain ask your insurance company.

My insurance company won’t reimburse me for a therapy visit because I haven’t met my deductible. Is that a violation of the parity law?

A deductible is the overall amount that you must pay out of your own pocket per year before your health insurance makes any payments. Depending on your plan’s deductible, for instance, you may have to pay $500, or even $5,000, out of pocket before your insurance company will pay any claims.

Prior to the parity law, many insurance plans required patients to meet different and often higher deductibles for mental health services than for medical services. As a result of the law, a single deductible now applies to both mental health treatment and medical services. In some cases, your plan may pay for mental health treatment after you have paid part of your deductible but not cover physical health treatment until you have reached the full deductible.

My copay is $20 when I see my psychologist, but only $10 when I visit my primary care physician. Isn’t that against the law?

Not necessarily. The parity law requires copays for mental health services to be equal to or less than the copay for most—not all—medical/surgical services. In this case, for example, it’s acceptable to pay a $20 copay for a mental health visit and a $10 copay for a primary care visit, as long as your copay is $20 or more for most of the medical/surgical services covered by your plan.

My insurance company has only approved a certain number of therapy sessions to treat my disorder. Is this a violation of the parity law?

The parity law prevents insurers from putting a firm annual limit on the number of mental health sessions that are covered. However, insurance companies can still manage your care. Your plan may say, for example, that after 10 or 20 appointments with a psychologist, they will evaluate your case to determine whether additional treatment is “medically necessary” according to their criteria. This kind of management is generally permissible under the parity law if the company uses the same standards for determining mental health coverage as they use to decide what medical services to cover. But if the company terminates or reduces care much sooner than your psychologist thinks is appropriate, that could indicate a possible violation of the parity law.

My mental health provider won’t accept my insurance, even though I have mental health coverage. Why not?

Psychologists and other mental health providers can choose whether or not to accept insurance. Unfortunately, many insurance companies have not increased the reimbursement rate for psychologists in 10 or even 20 years despite the rising administrative costs of running a practice. Other companies have recently cut their reimbursement rates. As a result, some plans have trouble attracting mental health professionals to participate in their networks.

If your options seem limited and your insurance is provided through your employer, you might consider discussing your concerns with your human resources representative. He or she may take that into consideration when negotiating your company’s plan with insurance companies in the future.

My insurance covers out of network providers. What do I need to do get reimbursed for psychotherapy services?

If your health plan covers out of network providers for mental health services and you are seeing a mental health provider who does not accept your insurance, complete your insurance claim form and submit it along with the mental health provider’s invoice to get reimbursed. If you are unsure about your health plan’s claim procedures for out of network providers, contact your insurance company.

Who should I talk to if I think my insurance company is violating the parity law?

If you have concerns that your plan isn’t complying with the parity law, ask your human resources department for a summary of benefits to better understand your coverage, or contact your insurance company directly. Your human resource department can provide you with information about your coverage and may be able to put you in touch with a health care advocate who can assist in making an appeal. If other employees are having similar issues, your HR department may wish to keep track of the problems and work with the insurance company to ensure that benefits are meeting employee needs.

If you do not have an HR department or if your insurance is not provided by your employer, you may wish to speak with the insurance company directly. To reach out to your insurance company, check for a customer service number on the back of your insurance card. If you obtained your insurance through an insurance exchange, you may be able to get help from your state insurance commissioner.

If you still have unanswered questions or wish to file a parity complaint, visit the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to find the appropriate agency to assist. You can also call the EBSA toll-free consumer assistance line at (866) 444-3272. The federal government’s Consumer Assistance Program website is another good resource.

You may also visit the Parity Track website for information about mental health parity or links to state agencies, as well as other valuable resources. Note that this website offers you the chance to submit a complaint with them about your experience. Registering a complaint with Parity Track is not a substitute for filing an appeal or filing a complaint with a governmental agency. This information is used to influence policy.

Using your mental health coverage

Check with your human resources department or insurance company for specific details about your coverage. Here are some important points to consider:

Average Copay For Health Insurance 2020

- Check to see whether your coverage uses provider networks. Typically, patients are required to pay more out-of-pocket costs when visiting an out-of-network provider. Call your insurance company or visit the company’s website for a list of in-network providers.

- Ask about copayments. A copay is a charge that your insurance company requires you to pay out of pocket for a specific service. For instance, you may have a $20 copay for each office visit. In the past, copays for mental health visits may have been greater than those for most medical visits. That should no longer be the case for insurance plans subject to the parity law.

- Ask about your deductible. A deductible is the amount that you must pay out-of-pocket before your health insurance makes any payments. Depending on your deductible, for instance, you may have to pay $500 or even $5,000 out-of-pocket before your insurance company will begin making payments on claims. As a result of the parity law, your deductible should apply to both mental and physical health coverage.

- Talk to your provider. When you call to schedule an appointment with a mental health provider, ask if he or she accepts your insurance. Also ask whether he or she will bill your insurance company directly and you just provide a copayment, or if you have to pay in full and then submit the claim to your insurance company for reimbursement. If your provider does not accept insurance, ask about his or her payment policy.

Zero Copay Health Insurance

The full text of articles from APA Help Center may be reproduced and distributed for noncommercial purposes with credit given to the American Psychological Association. Any electronic reproductions must link to the original article on the APA Help Center. Any exceptions to this, including excerpting, paraphrasing or reproduction in a commercial work, must be presented in writing to the APA. Images from the APA Help Center may not be reproduced.